Read time: 10-12 min

Introduction

Welcome back to The Hut of Andre! This week we are picking up where we last left on the Stories of the World series.

Our last post studied one of the two oldest pieces of literature ever found, The Instructions of Shuruppak. This week we will dive into the other text, the Kesh Temple Hymn.

Just like The Instructions of Shuruppak, the Kesh Temple Hymn was written around 2500 BCE in Sumer and it speaks about the creation of the temple of Kesh (Kec) and praises the goddess Nintud. However, the Kesh Temple Hymn is of a completely different nature to that of The Instructions of Shuruppak. When properly read, this text sounds majestic and transmits a sense of spirituality that connects to one’s deepest self. Just reading it gives the sensation that although written in the same period, the Kesh Temple Hymn does not belong to the same literary category.

What made these people start writing about religion? Was writing seen as something holy in Sumer? How come this liturgy still sounds like something we would hear on Sunday mass?

All of these we will discuss in this week’s post.

Setting Religion in Stone

We all know that before the invention of writing religion was passed down to generations orally. At some point in time, this started to change, and religious marks and texts began to appear. First as symbols and signs on temples to mark which deity they related to. Then as time passed, writings of panegyric character started to appear, which would glorify cities, temples, gods and events.

The reasons why sacred writings appeared are not confirmed. One possibility is that it was to preserve religious teachings. The argument is that oral transmission lent itself to error since it relied on human memory. Writing down the religion meant that the message was recorded with perfection for perpetuity.

While that option is plausible, I believe this came after these texts started to appear. Oral transmission may be flawed, but writing does not come without its caveats. Documents can be forged or lost. Relying on writing for the communication of theology had the risk of diminishing the memory of such ideas. If these texts were to be lost, there was no way to recover the lost information (like it happened with the library of Alexandria). So while it is probably true that with time religion was written to be better preserved, there must have been a different reason for the appearance of religious texts.

A more probable cause is that it was something that carried out divine powers. Similar to some magical token or rune. To me, this explains better the progression from holy pictograms that were put at temples to represent their god/goddess to the writing of hymns that praised a particular city or hero. Similar to how churches have holy icons that represent Jesus and its specific patron, or how mosques have Quranic verses and Islamic calligraphy on their prayer halls.

The Kesh Temple Hymn is the perfect example of this, proving that these religious writings not only were believed to carry some divinity, but also that writing was considered something holy and divine by the Sumerians. This panegyric characteristics have led many to believe that this was a way of giving importance to a specific city in the Sumerian civilisation. Similar to the sanctification of a site in Christianity. So its written form would be sacred, like the bible, and was probably kept within the temples.

Writing as a divine gift

Religion has been tied to writing, at least, since the inception of literature. The Instructions of Shuruppak allowed us to investigate the beginnings of writing as a tool for accounting, ruling and trading. While currently this is the most accepted theory, it has not always been this way. Up to the 19th century, the creation of writing was always connected to some divinity. Daniel Defoe (writer of “Robinson Crusoe”) states how writing was given to humans by God in his book “An essay upon literature: or, An enquiry into the antiquity and original of letters”

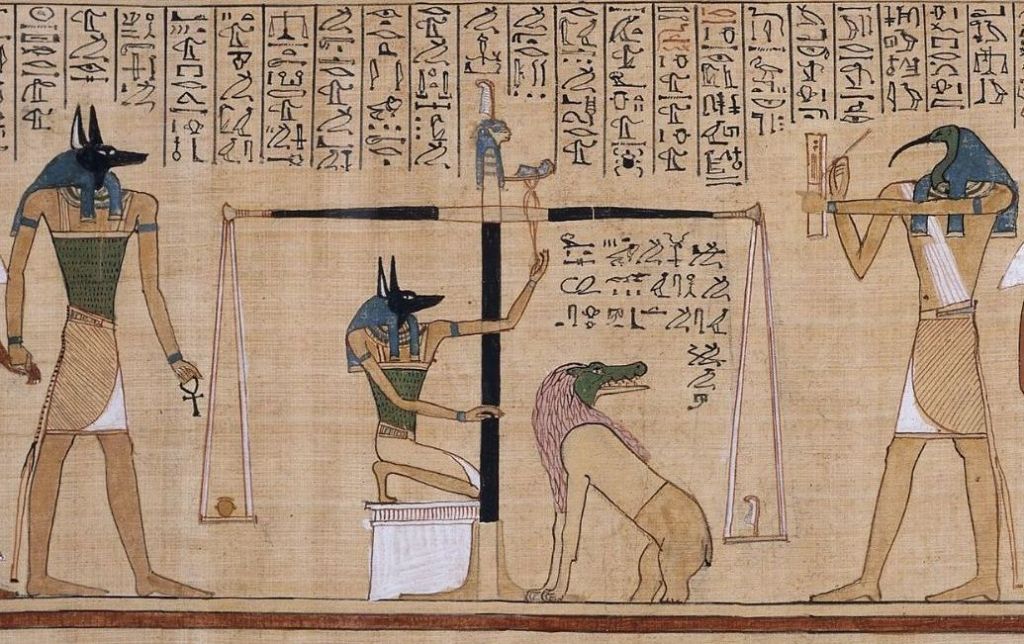

And this was not only in Abrahamic religions. We can see throughout time and cultures the description of writing as a divine gift. The Romans attributed the creation of writing to the God Mercury, the Roman version of the Greek God Hermes (the messenger of the Gods) who many related to the Egyptian God of writing Thoth. In Asia, the Chinese attributed the creation of writing to Fu Xi, and the Indians also connected the creation of writing to the divine. In the American continent, the Mayans credited the invention of writing to the God Itzamná. On their side, the Sumerians believed that writing was given to them by the goddess Nisaba. Yes, remember that scribe named Nisaba who supposedly wrote The Instructions of Shuruppak? It turns out I was wrong. She was not a woman, but a goddess instead.

From this, one cannot but wonder how did they all reach that conclusion. How come most past civilisations believed a divine power gave humans writing, while we know that is most probably not true? The theories to explain how link came to be are varied and, to date, none have been able to be confirmed. These theories can be boiled down to two groups: those who believe it was as a means of oppression and those who think it was an attempt to explain something unknown. There is as well a third group of people who consider the stories to be true. Either because or religion or because they entertain the idea that some superior being brought it to us. This last group we will on later posts when we know more about Sumerian mythology.

Modern sceptics believe that these stories come from priest and rulers, trying to increase their power and control over people. By connecting writing to the gods they established their respect, people would see them as holy, since they could understand and transmit the message of the gods to them. It would not have been the only time that humans connected themselves to the divine to strengthen their position.

Less dramatic theories suggest that this happened because the inception and development of writing were just not well documented. It was something that slowly developed, so people were not able to pinpoint its invention to a specific person or time. Similar to mathematics. This hypothesis argues that by the time writing really had a significant impact on people’s lives, nobody probably remembered how it had all begun. Believing no human could not have possibly invented it out of thin air, they connected it to divine providence.

While both theories are exciting possibilities, I believe the truth lies somewhere in the middle. We already know that writing was something that only the ruling elites could do. Thus, it is a perfect possibility that they would have benefited from linking writing to some divine power. However, for people to believe them, enough time should have passed for the population to forget how it started. Considering that, rather than a eureka moment, writing developed slowly over hundreds if not thousands of years, we can then understand how people, and even the ruling elite, could forget. So yes, rulers and priests could have very possibly created this theory for the inception of writing to gain more power over their subjects, but the fact that their population and even themselves had forgotten the truth of the events allowed this to happen.

The Kesh Temple Hymn – Praising the gods

The Kesh Temple Hymn, also known as The Liturgy to Nintud, is as we said, the oldest religious literary example found to date. The text is a eulogy both to the temple of Kesh and the goddess Nintud and containing 145 lines and separated in eight sections.

The first section starts with the creation of Kesh by the god Enlil (the chief deity of the Sumerian Pantheon). He comes out of the pantheon and lifts his look upon the lands. As this happens, the lands raise themselves, all corners of heaven turn green like a garden and the Temple appears over the lands. This is something straight out of a fantasy movie. One cannot help but be fascinated when reading this. The ability of the text to convey the message and transport the reader straight into the story is astonishing.

“The princely one, the princely one came forth from the house. Enlil, the princely one, came forth from the house. The princely one came forth royally from the house. Enlil lifted his glance over all the lands, and the lands raised themselves to Enlil. The four corners of heaven became green for Enlil like a garden. Kec was positioned there for him with head uplifted, and as Kec lifted its head among all the lands, Enlil spoke the praises of Kec.”

The Kesh Temple Hymn

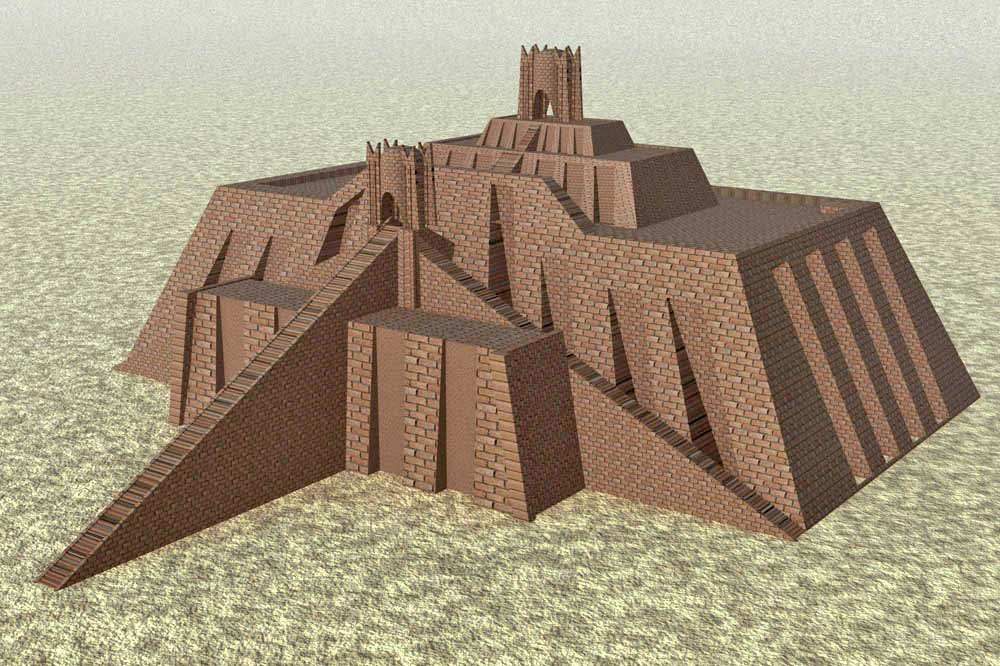

The story continues to describe how Nisaba (our good old’ Nisaba goddess of writing and wisdom) writes the story as it happens and describes the Temple. We understand from this that Nisaba is recording the events on a clay tablet, which reinforces the divinity of writing and the religious scriptures. Some authors point the similarities or the relationship between Enlil and Nisaba and the one between Yahweh and Moses. The description of the temple is superb, it gives a majestic representation of the temple, which reached “as high as the hills, embracing the heavens, growing as high as E-kur, lifting its head among the mountains!” and was rooted in Abzu (cosmic underground waters) which probably tries to represent that it reaches the underworld.

“Growing as high as the hills, embracing the heavens, growing as high as E-kur, lifting its head among the mountains! Rooted in the abzu, verdant like the mountains!”

The Kesh Temple Hymn

The section finishes praising the goddess Nintud (the Sumerian mother goddess and one of the creators of humankind) as well as Kesh and Nintud’s hero son Acgi. This line is how all other sections of the hymn finish, the reason why the text is also called Liturgy to Nintud.

“Will anyone else bring forth something as great as Kec? Will any other mother ever give birth to someone as great as its hero Acgi? Who has ever seen anyone as great as its lady Nintud?”

The Kesh Temple Hymn

The following two sections go on describing the Anunnaki as lords of the temple, as well as the size of the temple using Sumerian metric scales “car” and “bur”. I was not able to find the meaning of “car”. On the other hand, “bur” is recorded as a measurement of area, that was done by counting the number of bricks that fitted in the area. So using the the dimensions of the smallest sumerian bricks at the time I could calculate that the area of “5 bur” described in the hymn would be approximately 175 hectares. That is more than three times the base area of the pyramid of Giza!

The hymn then spends the next two sections focusing on the temple’s interior, exterior and gives a description of who is within it and what rituals they do. It starts by with the heroes going inside the temple to perform the “oracle rites” and herds of sheep and cattle gathered for sacrifice. Again we see in Sumer, practices that will be carried out by cultures across time even to date such as the importance of oracles in giving wise counsel and the sacrificial offerings to gods to win their favour.

As the hymn focuses on the interior of the temple, Nintud (AKA Ninhursaja) is described as sitting “like a great dragon”, Cul-pa-ed (Nintud’s spouse) as being the lord of the house and their hero son, Acgi, consuming the contents of vessels. That clearly shows that the Kesh Temple is dedicated to the goddess Nintud and her family.

“House Kec, given birth by a lion, whose interior the hero has embellished (?)! The heroes make their way straight into its interior. Ninhursaja sits within like a great dragon. Nintud the great mother assists at births there. Cul-pa-ed the ruler acts as lord. Acgi the hero consumes the contents of the vessels (?). Urumac, the great herald of the plains, dwells there too. Stags are gathered at the house in herds.”

The Kesh Temple Hymn

The sixth section talks about the temple’s exterior appearance. The Kesh temple is described as having a lion reclining on his paws at the entrance, a wild bull on its bolt and Laḫmu deities supporting its terrace, probably in the shape of half-columns. In the seventh section, the hymn describes the songs played and the instruments used at the temple. It shows religion and music have a deep link, as the author Laurence de Rosen stated: “Since the dawn of time, music has been our medium of communication with its divinity/divinities.” The hymn also gives us an insight into the instruments used at the time. It is fascinating to see that they used wind, percussion and string instruments. Categories that did not change for five millennia, until the appearance of electronic instruments. The music described in the hymn is solemn and spiritual, close to the sort of music you may have heard on a Viking ritual.

“The bull’s horn is made to growl; the drumsticks are made to thud. The singer cries out to the ala drum; the grand sweet tigi is played for him.”

The Kesh Temple Hymn

The final section, or eighth house, ends with a warning and invocation to approach the temple. This admonition is repeated four times and with it, the text ends. Many authors say this sort of ambivalence about approaching temples has influenced Christianity and Judaism. However, I do not know enough to confirm that and so, this last section is the most obscure and mystic to me. It leaves me questioning its intention and why it is there. I guess it is something we will learn more of as we keep digging into Sumerian and Semitic texts.

“Draw near, man, to the city, to the city — but do not draw near! Draw near, man, to the house Kec, to the city — but do not draw near! Draw near, man, to its hero Acgi — but do not draw near! Draw near, man, to its lady Nintud — but do not draw near! Praise be to well-built Kec, O Acgi! Praise be to cherished Kec and Nintud!”

The Kesh Temple Hymn

Conclusion

This hymn was a new experience. Just as much as The Instructions of Shuruppak surprised me by the relevance of its teachings, the hymn’s capability to transmit this sense of divinity shocked me. Just in the first section, the solemnity of the hymn can be seen. Its repetitions, exclamations, praises and metaphors make the effect of the text go beyond just the story. The reader can imagine this hymn being recited in ancient Sumerian out loud in a temple, with the growl of horns, beats of drums and notes from the “tigi” and be overcome with the sensation of spirituality it transmits, even though we would not understand what it says. Five thousand years after its inception, we recognise the feeling these people felt when listening to these hymns and see, once again, that our connection to them is not so distant.

The other fact which does not go unnoticed is the ability of the liturgy to transport us to the events. The metaphors and descriptions allow the reader to imagine the temple and its creation in all its majestic splendour. We tend to think of writing as an essential tool for literature, but the reality is that the written works we study are just the mere reflection of an oral art developed since the start of times, oral literature.

Having read The Instructions of Shuruppak and the Kesh Temple Hymn has opened my mind and set a base to understanding the texts we will study in future posts. We have come to better understand the relationship between writing and cultures, how literature came to be, what forms it took and what function and power it had for the people of the most ancient civilisation known to mankind. We keep seeing, just as in our last post, that our deepest cultural roots come from the Mesopotamian people of the Bronze Age and before.

Our next steps will take us through the next item on our chronological list: “The Pyramid Texts” from Egypt. We will be able to compare these texts to what we already know from Sumer and study the literature of this other ancient civilisation which has interested our modern world for more than one hundred years.

See you next week!

Bibliography

- Biggs, R. D., and J. N. Postgate. “Inscriptions from Abu Salabikh”, Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G.. “The Kesh Temple Hymn”, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998.

- Bywater, M.E.. “The Impact of Writing: Ancient and Modern Views on the Role of Early Writing Systems Within Society and as a Part of ‘Civilisation’”, UCL.

- Cristian Violatti. “The Divine Gift of Writing”, Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 24 Feb 2015

- Museum, Trustees O. T. B. “Scribes in ancient Mesopotamia”, Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 03 Aug 2011.

- Mark, Joshua J. “Nisaba”, Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 23 Jan 2017.

- Kadim Hasson Hnaihen. “The Appearance of Bricks in Ancient Mesopotamia”, Athens Journal of History – Volume 6, Issue 1, January 2020 – Pages 73-96

- de Rosen L. (2014) “Music and Religion”. In: Leeming D.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion. Springer, Boston, MA.

- Mark, Joshua J. “Sumerians”, Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 09 Oct 2019..

- Thorkild Jacobsen. “Mesopotamian religion”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. 07 March 2016

Pingback: Torah VS The Old Testament: What Is The Difference Between Them?-(Facts & Distinctions) – All The Differences